Mathematik-Online-Lexikon:

|

[Home] [Lexikon] [Aufgaben] [Tests] [Kurse] [Begleitmaterial] [Hinweise] [Mitwirkende] [Publikationen] |

|

Mathematik-Online-Lexikon: | |

Kurvenintegrale und konservative Vektorfelder |

| A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z | Übersicht |

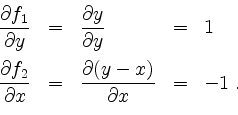

Berechne jeweils das Kurvenintegral von ![]() längs

längs ![]() . Ist das Vektorfeld

. Ist das Vektorfeld ![]() konservativ?

Berechne gegebenenfalls eine Stammfunktion von

konservativ?

Berechne gegebenenfalls eine Stammfunktion von ![]() .

.

Lösung.

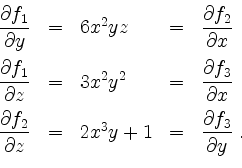

Also erfüllt

Das Kurvenintegral von ![]() längs

längs ![]() ergibt sich zu

ergibt sich zu

![\begin{displaymath}

\begin{array}{rcl}

\displaystyle\int_\gamma f

&=& \displayst...

...{3}\right]_0^2\vspace*{2mm}\\

&=& \dfrac{16}{3}\;.

\end{array}\end{displaymath}](/inhalt/beispiel/beispiel1140/img12.png)

Ferner ist der Definitionsbereich von

Wir wollen nun eine Stammfunktion ![]() von

von ![]() berechnen. Hierzu iteriert man ,,partielles Aufleiten``.

berechnen. Hierzu iteriert man ,,partielles Aufleiten``.

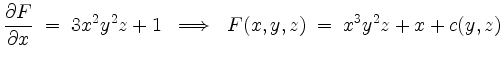

Zunächst wird

mit einer stetig differenzierbaren Funktion

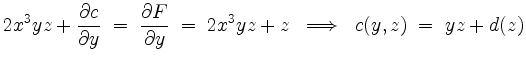

Weiter gilt

für eine stetig differenzierbare Funktion

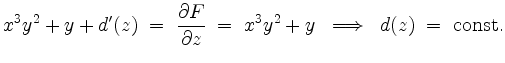

Schließlich gilt

Wir können also

Diese ist nur bis auf eine additive Konstante bestimmt.

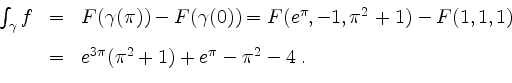

Nach dem ersten Hauptsatz für Kurvenintegrale wird nun

siehe auch:

| automatisch erstellt am 11. 8. 2006 |